In the second of our Gilmore Insights blog post series, Music Librarian for Reference and Instruction, Suzanne Lovejoy, discusses one of the most popular and enduring songs of World War I, "There’s a Long, Long Trail A-Winding". Suzanne outlines the history of the song, including its connection to Yale, and the wealth of collection materials both in the Music Library and throughout Yale University Library related to it. Suzanne has been at Yale since 1993 and during that time has become an invaluable asset to students, faculty and other researchers working with our collections, notably our special collections. So without further ado..over to Suzanne.

“There’s a long, long trail a-winding / Into the land of my dreams / Where the nightingales are singing / And a white moon beams.

There's a long, long night of waiting / Until my dreams all come true / Till the day when I’ll be going / Down that long, long trail with you.”

Although these lyrics may seem uncharacteristic for a war song, they are from the chorus of one of the most popular and enduring songs of World War I. And the song had its origins here at Yale, in Connecticut Hall, when Zo Elliott (YC 1913) Stoddard King (YC 1914) collaborated on it so that they might attend, all expenses paid, the Zeta Psi banquet in Boston in the spring of 1913. The “lugubrious ditty” (as King styled it) went over well – the Zetes stopped throwing bread, listened attentively, and joined in the final chorus. A Boston publisher in the audience encouraged them to publish it, and so King shopped it around several New York publishers, but no one was interested.

Early copies of the song, correspondence relating to it, and several documents pertaining to it are included in the Zo Elliott Papers, MSS 18, in the Gilmore Music Library. Further documentation can be found in articles written by Elliott in later years, in contemporary newspaper accounts available through several full-text subscription databases, including ProQuest Historical Newspapers and the Times Digital Archive, and through Yale class histories and obituaries in the Manuscripts and Archives Department of Sterling Memorial Library. Then there are the many recordings of the song, in the Collection of Historical Sound Recordings and the Music Library Recordings Collection, in archives and digital sound archives elsewhere, in subscription audio databases such as Music Online from Alexander Street Press and Naxos Music Library, and on YouTube. Additional copies of the sheet music may be found in the Music Library’s Vocal Sheet Music Collection and in the World War I Collection in Manuscripts and Archives.

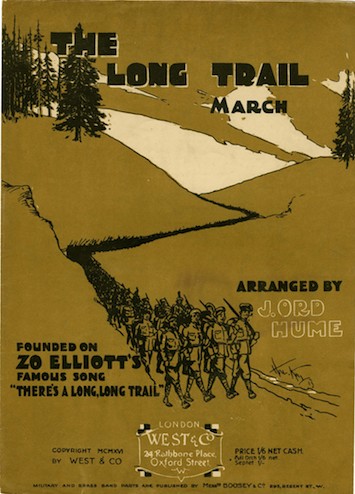

Following graduation, Zo Elliott attended Trinity College in Cambridge, playing the song on his neighbor’s piano at parties, occasionally accompanied on the violin. Eventually, Claude Yearsley of the small publishing firm West Ltd. in London heard it and, with half the publication cost covered by Elliott’s mother, brought it out early in 1914. Yearsley worried for some months whether he would ever recoup his investment. Eventually the problem became keeping up with demand.

Elliott told how the song first attracted widespread attention when “a boatload of Canadian soldiers sang it coming down the Thames from a Sunday outing.” Soon it was picked up by others, and British Tommies marched off to war with it and sang it constantly, waiting in the trenches and going “over the top.”

Wartime Accounts

One remarkable account from the Times of London concerns the transport vessel Tyndareus, which struck a mine and began sinking in February 1917, off Cape Agulhas, South Africa. A battalion of the Middlesex Regiment was on board and was called to assembly after the accident. They stood in formation and remained in order, even as the propeller rose out of the water and doubt ensued whether help would arrive in time. “As soon as the roll had been called, and the order ‘stand easy’ given, someone started ‘The Long, Long Trail,’ and in a few seconds the whole of the gathering, from end to end of the ship, had taken up the refrain of the latest marching song. Then came the old favourite ‘Tipperary,’ and for half an hour afterwards, while an ominous incline of the deck towards the bows became more and more noticeable, chorus after chorus swept along the lines, while both the X, and the Y, were racing to the rescue.” Rescue ships arrived in time and all hands were saved.

The English poet John Masefield, in his acceptance speech for the honorary LL.D. awarded by Yale in June 1918, told the following: “One day, during the Battle of the Somme, I passed down one sector of the British line. The boys were singing, and they were singing a song written by a Yale man: ‘There’s a long, long trail a-winding to the land of my dreams.’ That is the most popular song in the British army today.”

One of those at the Somme was an Englishman serving in the Canadian Field Artillery, Lieutenant Coningsby Dawson. In one of his letters from the front, dated Oct. 18th, 1916, he wrote:

We've fallen into the habit of singing in parts. Jerusalem the Golden is a great favourite as we wait for our breakfast—we go through all our favourite songs, including Poor Old Adam Was My Father. Our greatest favourite is one which is symbolising the hopes that are in so many hearts on this greatest battlefield in history. We sing it under shell-fire as a kind of prayer, we sing it as we struggle knee-deep in the appalling mud, we sing it as we sit by a candle in our deep captured German dug-outs. It runs like this:

"There's a long, long trail a-winding…." [He quotes the complete Chorus.]

You ought to be able to get it, and then you will be singing it when I'm doing it.

The Song Comes to the United States

Americans learned “There’s a Long, Long Trail,” too, as it was published in the U.S. by Witmark and Sons in 1914, but it didn’t become widely popular here until 1917. The American publisher changed the song, reharmonizing the verse from minor to major, and transforming it into a ballad rather than a marching song. Several early examples of the American version can be heard in recordings available online. The Victor recording by tenor James Reed and baritone J. F. Harrison from September 1915 is one of the earliest American recordings (Alexander Street Press; YouTube). A second recording, also for Victor by the Irish tenor John McCormack, recorded on June 7, 1917, surely helped popularize the song with Americans (available on Alexander Street and YouTube).

Following the American declaration of war, the song was used as a recruiting tool, as when Canadian Highlanders came marching down Broadway in New York in July 1917; in fundraising concerts sung by classical artists such as Ernestine Schumann-Heink, Enrico Caruso, Alma Gluck, and McCormack; in vaudeville shows; within concerts prior to film showings; and spontaneously by great crowds at gatherings. Elliott’s fellow recruits sang it at the Officer Training Camp in Plattsburgh, where many Yalies went following enlistment. “I remember the remarkable sensation of hearing my tune start with the big fellows up front, pass through my own squad, reach the end of the column, and then be taken up by the next company.” The song, played by military bands, accompanied the men embarking on ships bound for France and those lucky ones who disembarked following the war.

Zo Elliott’s term as an officer in training lasted only five weeks – he was discharged on medical grounds and spent the summer in New York. But he was successful in re-enlisting as a private in the Signal Corps, and encountered soldiers singing the song at Camp Vail in New Jersey. Stoddard King, who had returned to Spokane, Washington, following graduation, and was married with two children, registered on the first day of the draft, June 5, 1917. His registration card can be seen online. He served in the Washington National Guard from May 1918 to November 1921. King and Elliott collaborated on several other songs before King’s untimely death in 1933, though none achieved the popularity of “There’s a Long, Long Trail.” Elliott continued studying and writing music, his last effort being an opera based on the life and legends of Billy the Kid titled “El Chivato.” He died in 1964.

Post-War

The song has lived on through the decades following the war. It has appeared in film soundtracks from 1929’s The Unholy Night to 2008’s Leatherheads, frequently uncredited. It got another lease on life during the Second World War, in For Me and My Gal with Judy Garland and Gene Kelly in 1942 and in Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo from 1944. Younger audiences have learned the song from television shows such as It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown (as heard by Snoopy, the WWI flying ace), M*A*S*H, and The Waltons, and in more recent series that look back to the “Great War” such as Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries and The Crimson Field.

Many notable recording artists have also performed the song over the decades: singers Gracie Fields, Bing Crosby, Rosemary Clooney, and Frank Sinatra, to name a few; popular groups such as Roy Rogers and The Sons of the Pioneers and The Kings Men; and military groups such as the British Legion Choir, the Band of the Scots Guards, and the US Marine Band.

Awards and Recognition

Yale awarded the Francis Joseph Vernon Prize for Poetry to Elliott and King in 1918, the first time ever to a popular song. The award went to “a work by Yale men that best represents the spirit and ideals of Yale." But Elliott also recalled other recognitions that meant a lot: the band playing “Long, Long Trail” and other songs as British troops marched over the Rhine following the Armistice; Coningsby Dawson’s letter quoted above; and the honor having a copy of the manuscript placed in the Hall of the Allies at the Army Museum in the Hotel des Invalides in Paris, along with a letter praising the song from a close friend, Dan Keller, who had died in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

The accounts above document what singing and hearing this song and similar songs meant to the troops enduring a long and savage war: the song served as more than a pastime to while away the long hours of waiting; it became a means to quell the fears of imminent destruction, to relieve the tensions of battle and horrible living conditions, to feel solidarity with one’s buddies while working and marching, to express the hope of returning home to loved ones, and occasionally to share a moment of common humanity with the enemy.

It seems appropriate to close this piece with words Elliott wrote in an essay titled “What Music Has Meant to Me.”

Every year that I am in France, I try to go up to the Argonne. Sometime I hope that someone will write what those fields are saying. The earth is singing there of loyalty, and courage, of longing for Mothers, and of sweethearts, and sons and daughters. The cuckoo can be heard in the early morning, as the mist rises from the fields, but there is something deeper. There are the voices of ghosts too, and they seem to be saying “Come pardner, give us a Song.”

Suzanne Eggleston Lovejoy

With thanks to Judith Schiff, Richard Boursy, and Jonathan Manton.