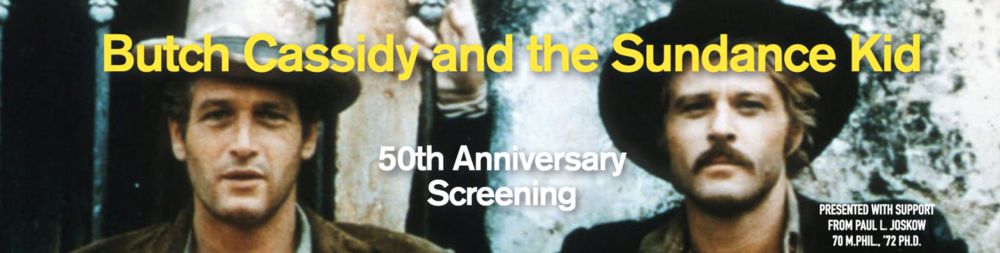

Film Notes: BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID

BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID, 50th Anniversary Screening

7 p.m. Friday, September 27, 2019

53 Wall Street Auditorium

Co-presented with the Democracy in America film series, with an introduction by Michael Kerbel and Matthew Jacobson and post-screening discussion with Joel Pfister

Film Notes by Michael Kerbel

PDF

Directed by George Roy Hill (1969) 110 mins

Screenplay by William Goldman

Cinematography by Conrad L. Hall

Music by Burt Bacharach

Produced by 20th Century Fox

Starring Paul Newman, Robert Redford, Katharine Ross, Strother Martin, Henry Jones, Jeff Corey, George Furth, Cloris Leachman, Ted Cassidy, and Kenneth Mars

On September 23, 1969, BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID had its world premiere a half-mile from here, at the Roger Sherman Theatre (now College Street Music Hall), thanks to director George Roy Hill (Yale College, 1943). The theatre accommodated about 2,000, but 5,000-6,000 people showed up, hoping at least to glimpse the numerous attending celebrities, including Paul Newman, Robert Redford, Joanne Woodward, and Barbra Streisand.

The film opened nationwide the next day and went on to become the year’s biggest box-office success. It won four Oscars, was selected for the National Film Registry in 2003, and is a landmark in the history of the western. Its legacy includes the names of Redford’s organizations dedicated to independent filmmakers–the Sundance Film Festival (founded 1978) and the Sundance Institute (founded 1981)–and Newman’s Hole-in the-Wall Gang Camp (founded 1988), which provides free on-site and outreach support for seriously ill children and their families.

The opening credits appear alongside a sepia-tinted silent film about Butch and Sundance that resembles Edwin S. Porter’s THE GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY (1903). Porter’s work, which was contemporaneous with the gang’s own train robberies, was the start of U.S. narrative film (and of the western genre). The first sound in BUTCH CASSIDY is of a movie projector, making us aware of the filmic apparatus and perhaps reminding us that Hill’s film is itself a fictional representation. Scriptwriter William Goldman’s proclamation, “Most of what follows is true,” is tongue-in-cheek: Butch, Sundance, and Etta existed, and many of the events actually occurred, but “what follows” is another movie legend.

It was an appropriate legend for the late 1960s. The assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy, the election of Richard Nixon, and the seemingly endless War in Vietnam had brought U.S. society to a peak of disillusionment and protest. Reflecting the era, Hollywood produced numerous revisionist approaches to long-established genres, presenting outlaws as antiheroes, lawmen as villains, and countercultural attitudes toward conventional American values. The western genre, which had been Hollywood’s most durable expression of traditional ideology, was particularly ripe for revisionism, e.g. THE WILD BUNCH, released three months before BUTCH CASSIDY. Significantly, the second and third biggest hits of 1969, MIDNIGHT COWBOY and EASY RIDER, though not westerns, contained many allusions to the genre and questioned its underlying mythologies.

BUTCH CASSIDY far surpassed these films commercially (adjusting for inflation, it’s the 39th biggest film of all time) because it packaged revisionism in audience-friendly ways. Goldman’s Oscar-winning script (for which he received the then-record sum of $400,000) is peppered with 60s-hip dialogue and amiable banter; and the film mixes comedy and violence, inept robberies and old-fashioned heroics. There are also entertaining French New Wave-influenced interludes: the lovely still-photo New York City montage; and the bicycle scene, with its absence of diegetic sound, substituted by the anachronistic Burt Bacharach-Hal David song, “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head” (which won the Oscar and was a #1 hit).

Above all, the film featured three of the era’s most glamorous stars. Katharine Ross had made a big impact in THE GRADUATE (1967), and her character is more prominent than is usual for a woman in a buddy film (although her introduction is uncomfortable to watch). Paul Newman was the leading man of the 1960s, with antiheroic roles such as Fast Eddie (THE HUSTLER), Hud, Harper, and Cool Hand Luke. Hill pays tribute to Newman in the opening sequence by focusing mostly on the actor’s face (and making us wonder when the sepia will turn to color so we can see those blue eyes). The subsequent introduction of Sundance is a three-minute medium closeup. Redford had been in movies for almost a decade, but initially was considered not important enough to be cast in this film. Sundance was his breakout role, and Hill’s lengthy shot is a way of saying, “Look carefully: a star is being born.” Newman and Redford had such winning chemistry that Hill reunited them for the even more popular THE STING (1973).

DID YOU KNOW: George Roy Hill was so devoted to his alma mater that he made Yale an unprecedented donation: the complete production record of BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID, including script drafts, financial records, memos, costume designs, storyboards, set models, and on-set photographs. The collection, supplemented by material from Hill's subsequent SLAUGHTERHOUSE-FIVE and THE WORLD ACCORDING TO GARP, is in 197 boxes (250 linear feet), and is available to researchers at Yale Library's Manuscripts and Archives.

Presented in the Treasures from the Yale Film Archive series with support from Paul L. Joskow '70 M.Phil., '72 Ph.D. Printed Film Notes are distributed to the audience before each Treasures screening.