The Yale Film Study Center has been awarded a $24,000 matching grant from the National Film Preservation Foundation to preserve Street Corner Stories, an iconic 1977 documentary produced by filmmaker Warrington Hudlin ’74 in New Haven.

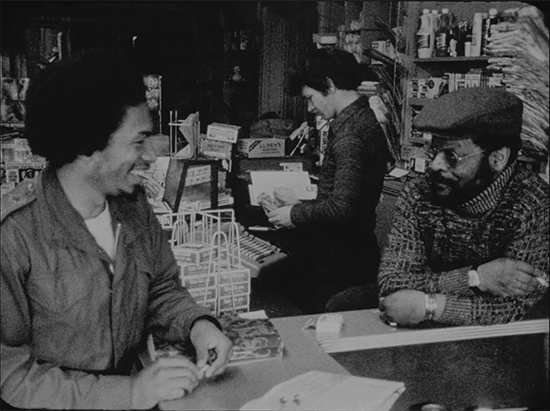

In Hudlin’s film, convenience store employees, customers, Yale employees, neighborhood kids, and others mix and meet at a New Haven convenience store, sharing jokes and stories, drinking coffee, and talking politics. Shot in cinéma vérité style, the film documents a unique storytelling form, an African American street-corner vernacular that Hudlin presents as a spoken form of the blues.

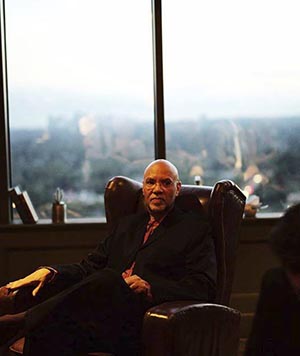

“Street Corner Stories captures a particular story of New Haven and Yale and the interaction between them at a particular point in time,” says Brian Meacham, the center’s archive and special collections manager, who is overseeing the preservation project. “It’s also an important film to preserve in light of Warrington Hudlin’s role in the development of black filmmaking over the last four decades.”

Hudlin was born in East St. Louis, Ill., in 1952 and came to Yale in 1970. During his senior year, he was named to the Scholars of the House program, an honor that came with the responsibility of creating an “essay or project which must justify by its scope and quality the freedom which has been granted.” Hudlin chose to make a film, eventually called Black at Yale: A Film Diary, which grew out of his own “split-consciousness experience” of being an African American student at Yale in a time of heightened political awareness and tension. The Film Study Center preserved Black at Yale in 2017.

Hudlin was born in East St. Louis, Ill., in 1952 and came to Yale in 1970. During his senior year, he was named to the Scholars of the House program, an honor that came with the responsibility of creating an “essay or project which must justify by its scope and quality the freedom which has been granted.” Hudlin chose to make a film, eventually called Black at Yale: A Film Diary, which grew out of his own “split-consciousness experience” of being an African American student at Yale in a time of heightened political awareness and tension. The Film Study Center preserved Black at Yale in 2017.

Street Corner Stories grew out of one of the final scenes (pictured below) in Black at Yale, in which one of the film’s main characters stops by a convenience store at the corner of Lake Place and Dixwell Avenue and falls into conversation with some of the regulars about their perceptions of Yale.

“That introduced me to them and their willingness to be on camera,” Hudlin recalls. “And given that I’d just made a film about the university and the black, privileged students’ point of view—I said, what do the people of New Haven think, what do the working class folks think? That became my next P.O.V.”

With funding from the National Endowment for the Arts’ then-new folk art division, Hudlin returned to New Haven in 1976 and began shooting the film in and around the same store. “Men would stop there on the way to work, to get a coffee and a doughnut,” Hudlin says. “It was kind of a launching pad or waiting room before going to work. People who had jobs, for the most part, but most importantly, had a point of view about life, circa 1976.”

The interactions Hudlin captured resonate with the “up-South” accents and sensibility he grew up with in East St. Louis, another community shaped by the post-World War II migration of African Americans from the rural South to the industrial North. Hudlin’s affinity for the blues, jazz, and rock and roll originated there, too; his neighborhood was home to Ike and Tina Turner, Miles Davis, and the gospel singer Brother Joe May.

In his first year at Yale, he read Ralph Ellison’s essay “Richard Wright’s Blues,” which introduced him to the idea of the blues “as more than a musical form, as an aesthetic and sensibility, an essential view of the world.” Six years later, he brought Ellison’s concept of the blues as a form of storytelling to Street Corner Stories.

The men he filmed, he says, “we're talking on that street corner about their wives and girlfriends, about the people who controlled their working life, about politics, race, the police, all the topics they sing about in the blues. I let people see the connections.”

The film premiered with a screening at the York Square Cinema in New Haven and subsequently screened on the domestic and international festival circuits, where it was well received. One contemporary reviewer called it “an excellent study of black language styles and story-telling.” In recent years, however, the film has been little seen, with only a few known copies.

In 1978, Hudlin and two fellow Yale graduates, George Cunningham ’83 Ph.D. and Alric Nembard ’73, co-founded the Black Filmmakers Foundation, a non-profit that supports and advocates for black filmmakers. As president of the foundation, Hudlin has mentored generations of young filmmakers. He is also a producer, director, writer, and actor whose credits include House Party (1990), Boomerang (1992), and Cosmic Slop (1994).

“I realize now that when I came into the world as a filmmaker it was like walking into a field that had not been plowed,” Hudlin says. “I took Street Corner Stories to an art house in New York. The person there asked what language it was in. I said English. And they said, will you have subtitles?

“We had no access even to independent art houses. We created the first ever black distribution cooperative because we knew colleges and campuses wanted to see our work, but they couldn’t get it. That’s why my background is so hybrid. I had to be writer, producer, distributor, marketer, all those things. If I didn’t do it, it wouldn’t get done. In those days, it wasn’t a glass ceiling. It was a steel and concrete wall.”

The Yale preservation project will use the original and best surviving elements of the film, donated to the Film Study Center by Anthology Film Archives in 2017. Hudlin had given the center a collection of original interviews, trims, outs, and audio elements for the film in 2014, but it was only when preservation work began on Black at Yale in 2016 that the original A/B rolls and optical track negative for Street Corner Stories came to light among a trove of materials Anthology had rescued years earlier from a defunct film lab.

Now, Fotokem, one of the last remaining film labs in the United States, is creating a new 16mm black and white duplicate negative of Street Corner Stories. Audio Mechanics, an audio restoration lab, will capture and digitally restore the film’s audio, and DJ Audio, specialists in film sound, will create a new optical track negative. Fotokem will create a new 16mm print for screening as well as a high definition digital scan of the new internegative to create a digital access copy of the film.

Last Fall, after the Film Study Center completed the preservation of Black at Yale, Hudlin returned to campus for a screening and discussion with students. The students’ varied responses made Hudlin realize the extent to which the issues that interested him as a young filmmaker remain relevant and unresolved. “The dual consciousness continues,” he says. “It’s the relationship of black people to America.”

Preferring to focus on the future, Hudlin does not spend a lot of time looking back at his earliest films, but he is glad that Yale is preserving them. “It’s history,” he says. “Unless these details are preserved, you can’t get accurate history.”

The Yale Film Study Center supports teaching, learning, and research, and fosters film culture at Yale through collection, preservation, access, and exhibition. The center has been part of Yale University Library since 2017. The National Film Preservation Foundation, a nonprofit created by the U.S. Congress to help preserve America’s film heritage, has awarded eight preservation grants to the center and the library since 2008.